|

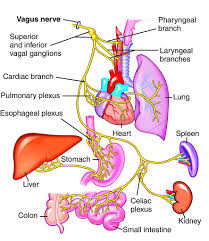

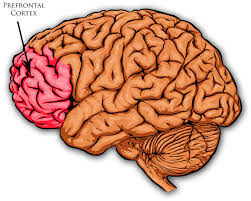

Recently, I read 'The Interpersonal Neurobiology of Group Psychotherapy and Group Process' edited by Susan Gantt and Bonnie Badenoch. The text is an exploration into two fields of psychology that excite me: group therapy and neurobiology. Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB) is a recent theory of mind that seeks to define mental health through a multi-disciplinary study of biology, cognitive science, anthropology, mathematics, sociology, and more. Psychologist Daniel Siegel coined the term Interpersonal Neurobiology and created the acronym FACES to define the characteristics of a healthy mind: flexible, adaptive, coherent, energized, and stable. The centerpiece of a healthy mind is coherent life narrative that makes sense to us as well as to others in our life. Group therapy began as an efficient way for therapists to treat the boatloads of soldiers returning from WWII and needing therapy to process their experiences. Since that time, group therapy has blossomed into a mode of treatment that is seen as effective as individual therapy and in some ways, superior to it. Since the roots of our suffering often began in our early family experiences and our own day-to-day difficulties manifest in our close relationships, group therapy offers us a microcosm of the people that shape our personality. In the first chapter of 'The Interpersonal Neurobiology of Group Psychotherapy and Group Process' the authors Bonnie Badenoch and Paul Cox explore the neurobiology of a coherent life as it relates to group therapy. Coherency represents the centerpiece of IPNB mental health because it is the summation of multiple steps of neural or brain integration. Brain integration equates to a healthy and happy person. By finding the words to describe our internal thoughts and feelings, we are integrating many aspects of ourselves. This process begins with emotion and culminates with words and meaning. As we tune into our bodily sensations and feelings, energy travels up our spine and nerves into our limbic system and passes through our amygdala - a brain structure that regulates mood and emotion. The amygdala and its associated vagus nerve have the capacity to kick us into fight-or-flight mode or to keep us calm and receptive to others. Our amygdala assesses for safety several times a second and sounds the alarm if things go awry. The alarm may be silenced by the hippocampus – the memory keeper of emotion and the structure representative of the next phase of brain integration. Part of assessing whether the present moment is dangerous or safe is comparing the present to the past. For example, if we open the door to a friend’s house to find a barking dog, our amygdala may default to a fight-or-flight state in order to protect us from a potential bite. However, the hippocampus may calm the amygdala by associating this moment to memories of this same dog being friendly and just overly excited. From body to amygdala to hippocampus energy lastly moves to our pre-frontal cortex where our felt sense of our history in our right brain hemisphere finds words and meaning in our left hemisphere. Up to this point, our experience is wordless, there are sensations, emotions, and memories, but no verbal meaning attached to them. The left pre-frontal cortex puts words to our experience and allows us to have autobiographical memory and a coherent life narrative. Successful integration of body to amygdala to hippocampus to pre-frontal cortex leads to self-awareness and a capacity for empathy for us as well as for others. In group therapy, we are invited into vulnerability and asked to put into words our here-and-now emotions and thoughts. From an IPNB perspective, group therapy allows our system to integrate previously dis-integrated experiences and find new meaning for old wounds while deepening our capacity for intimacy. These are all part of weaving a coherent life. For example, Bill was not allowed to be angry as child because his anger was amplified by his own mother’s inability to handle strong emotions. Bill’s complicated relationship with anger has manifested in his failed relationships with women that, over time, find him dispassionate, distant, and generally on ‘auto-pilot.’ Bill also suffers from chronic depression. Using the IPNB model to explain Bill’s challenges, we surmise that Bill’s early childhood was so overwhelming that his young brain was unable to integrate his experiences with anger and he has turned that same emotion inwards. Aspects of the brain develop in a hierarchy, from amygdala to hippocampus to pre-frontal cortex. So at the age of two, Bill’s amygdala (alarm system) was online but his hippocampus (emotional memory keeper) and pre-frontal cortex (meaning maker) were not available to help regulate him. So he has only wordless feeling states and behavioral impulses that unconsciously say to him ‘do not experience or express anger.’ In IPNB jargon, these are known as implicit memories – feeling states that have no memory attached to them. Since these feeling states are unconscious, Bill is unable to harness the regulating capacity of his hippocampus and pre-frontal cortex. So he remains silent and brooding in the group especially when a female member with a disposition similar to his own mother triggers him. Through his amygdala function, Bill notices sickness in his stomach and a desire to move away from what is happening internally. This is an early childhood feeling state for Bill – an implicit memory state. Through tone of voice, eye contact, and general attunement Bill stays with his feelings and begins to remember, through hippocampal functioning, certain instances of his mother being angry and causing him to ‘bottle up’ or swallow his feelings. Bill reflects on these experiences and sees how they have caused him so much pain in his relationships with women. Through integration with the pre-frontal cortex, Bill puts words to these experiences giving them meaning that he and the group can understand. Bill is beginning to feel the full spectrum of his emotions and to harness them as powerful messengers of his experience. His relationships feel more alive and nurturing and he views the symptoms of his depression in a healthier manner. The group has allowed Bill to experience his strong emotions without shaming thus allowing his brain to make new neural connections. These neural connections have attached new meaning to his implicit memory states and allowed the unconscious to become conscious. In short, his life is more coherent. Group offers us a chance to put new meaning to difficult feeling states associated with childhood or other difficult life experiences. Group members learn to trust that they can bring their full selves into relationships and use one another to make sense of the complexity of life. By inviting compassion and attunement into the group to hold powerful feeling states the brain finds new connections and heals itself.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

David HixonMy ongoing exploration into therapy related topics. Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed