|

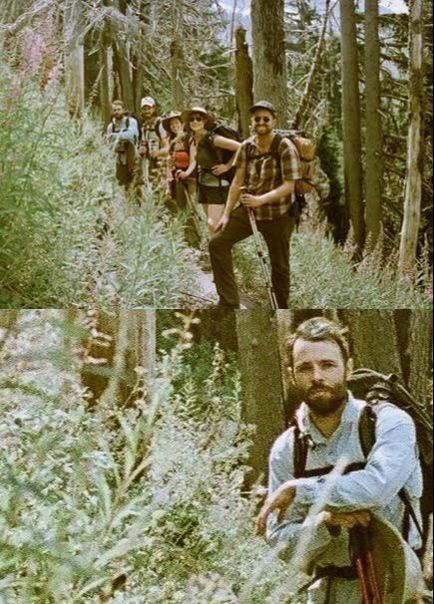

For the past 6 years, my close friends and I have taken a 5-day backpacking trip in some wild part of the world. What started as a one-time adventure through Teton National Park has now become a tradition of endurance and bonding. We walk 6-12 hours everyday carrying 35-40 lbs. packs above the tree lines of snowy mountains and alpine passes. When it’s time to camp, we pitch our tents, inflate our sleeping mats, filter water, and go through the long sequence of preparing our meals then cleaning up so as not to attract bears. Our shoulders, backs and knees groan as we crawl into our sleeping bags and hope rain or snow doesn’t fall too hard in the night. We repeat this sequence for 5 days. Why choose to exert so much effort and experience so much discomfort? Aside from the staggering scenic beauty, because there is a deep sense of accomplishment from being self-sufficient in a harsh environment, if only for a few days. Because the suffering in close proximity with my friends shows me my limitations and areas for improvement. And because sleeping, eating, and…. pooping (not necessarily in that order) with my friends gives me an ability to laugh with them at anything resembling a joke (thanks Mt. Niblet and Nub Peak). Usually the first few days of the experience feel like the relationships of my day-to-day life. I mostly regulate my emotions and myself and look out for my own well-being. As the group encounters both collective and individual hardship I see that others could use my help and I could use theirs. My friends’ mood soured on the second day when a rainstorm soaked their tent and sleeping bags. Some of us wanted a faster pace that day so we took the extra step of taking their sopping gear with us to dry in the sun. On the third day, I developed a monstrous blister on my heel and my girlfriend and friend carried much of my gear for the remaining 2 days. On an intellectual level, I agree that helping others feels good, but I often lose touch with this golden rule in my day-to-day life. Backpacking provides a plethora of opportunities to ask for help and to give it. Like the insights gathered in meditation, the only lessons I really learn are the ones I actually experience. While the physical actions of helping others are clear and obvious to me: fill their water, give them a Tylenol, and share my stash of nuts.com snacks. The psychological, emotional, and power dynamics are more obfuscated and have required me to engage in some deeper introspection. I like control. My day-to-day routine takes the guesswork out of what I should be doing at any moment. Because of the consistency, it is easy for me to anticipate and solve problems and knock out my responsibilities. To borrow some language from author Michael Pollan, the reason this strategy is effective is because there are no surprises. And the reason this strategy isn’t effective is because there are no surprises. At times, life takes on a monotonous or droll feel because I’m not open to the connections or spontaneity around me. This tendency manifests itself in a more stark way on our backpacking trips. Typically, I plan the hikes for our group. This satisfies my need for control, but has also prohibited me from sinking into playful moments with friends because my mind is in ‘tasking mode.’ Much of the time, I feel executive responsibility for the trip even when no executive is necessary. In 2017, my partner and I quibbled because it was obvious that instead of enjoying Mt. Hood and my friends I was incessantly checking the map or time-to-sunset. I felt disconnected and alone. My chums clearly had the ability to read a map or track the sun, but I had difficulty trusting them. In the world of psychotherapy, there’s a lot of travel metaphors like ‘finding your compass’ or ‘walking your own path’ or ‘asking a guide’, so I appreciated the concrete symbolism of literally handing over the map of our route to my close friend at the start of our hike this year. Before we ventured into Banff National Park, he playfully informed me that I wasn’t allowed to answer questions about the details of our route. I had to defer to him. In a welcome power play, he established his role and mine. “Safety word is ‘Quasimodo’, Dave.” Losing control was (and still is) often difficult. At times, I disagreed with the consensus or felt lost in the crowd of 7. Occasionally, I became frustrated with my friends’ attitudes or their perceived lack of foresight (even in the face of my own). Sometimes I was moody or irritable because of pain in my feet or the unrelenting cold and wetness of the Canadian Rockies. Or those god damned thieving chipmunks! There was nowhere to hide my mood or my emotions. We ate, walked, and slept within feet of each other, 24/7 for 5 days. Thankfully, each new challenge while backpacking provided not just a potential for argument, but also a potential for repair and bonding. We could grumble, disagree and still laugh at each other’s horrendous ‘trail stink’ or share our last drop of water (but you can pry my cacao goji energy-squares from my cold dead hands). The whole endeavor of backpacking reminds me of what I’ve read of encounter groups of the 60’s and 70’s and what I’ve experienced in limited doses at group psychotherapy conferences. The precursor to modern interpersonal process groups, encounter groups were short (3-4 days) but intense in their nature. Members often spent 12-15 hours per day together or even slept in the same room with one another. The format differed widely from group-to-group, but generally there was emphasis on: here-and-now feelings towards one another; honesty; and confrontation. Some were muscularly guided by leaders, while the leadership of others was more egalitarian. The thrust of encounter-group theory was that spending sustained and intense amounts of time with others whittles down ‘defenses’ and allows complexes or disorders to manifest more quickly than in once-per-week therapy sessions. In other words, it pisses you off. The surfacing of these emotions allows members to make quick gains at the cost of being very uncomfortable for a few days. Unfortunately, research showed that while encounter groups could produce significant and occasionally dramatic change, it could be negative or positive in its direction. Pressure creates diamonds, it also breaks pipes and causes earthquakes. Many groups had high casualty rates (~30%) and actually harmed the long-term well-being of some of its members. This fact was especially true of groups that emphasized anger and confrontation or were guided by authoritarian or rigid leaders. According to esteemed process-group leader and author Irvin Yalom, M.D., a few important lessons on personal change in the context of relationships can be gleaned from these encounter groups. 1. Don’t just let it all hang-out, let more of it hang-out than usual if you are willing to analyze yourself 2. Getting out anger is helpful, but leaving it out is not 3. Individual learning and positive change correlates with group cohesion, group climate and role flexibility 4. High risk encounter groups produce high casualty rates – not higher gains 5. Don’t wait for understanding later, seek understanding now Yalom’s third point on cohesion is the most relevant to my experience backpacking. As the group spent more time with one another and collective challenges were faced, cohesion grew and my own willingness to look at my quirks increased. After hiking through 8 hours of snow and sub-freezing temperatures our 4th day, I felt closer than ever to my friends the following day. And collective decision-making became easier. While our morale occasionally dipped, I credit my friends’ individual ability to tolerate and even laugh at our own discomfort. Experiencing pain alone is miserable, facing it together was fun. Once again, I learned that sharing outside my comfort zone is a process of acceptance rather than rejection. The ability for me to toggle between occasional leader, follower, and member most-in-need-of-help gave me empathy for my friends whenever they switched into one of those roles. I took no offense when someone asserted we slow down and found it easy to lend my last pair of dry socks because I had lived the emotions intrinsic to those experiences. While backpacking through the mountains is not feasible for many because of money, physical ability, or various other factors, I believe the lessons extrapolated can be found elsewhere in life. In the world of psychotherapy, participation in some kind of relational counseling (couples or group therapy) can bring profound understanding to individuals. My deepest relationships say a lot about my own fears and boundaries and illuminate new areas for growth. The challenge of trusting others and myself especially around my extremes of anger, suffering, and love, is a continual point of work that surfaces in my own coupledom and my membership in a process group. Our yearly hikes serve as yardsticks to measure my own progress (or regress), but any commitment to self-inquiry could potentially serve the same purpose whether its meditation, yoga, or a creative pursuit. Backpacking has the added benefit of a scenic external setting to a powerful internal experience…and plenty of opportunities for snacking.

5 Comments

|

Details

David HixonMy ongoing exploration into therapy related topics. Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed