|

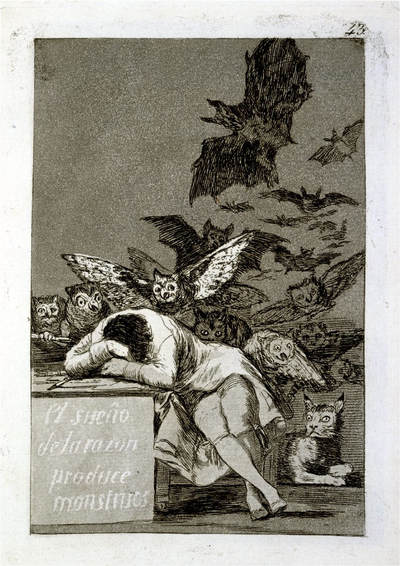

Michael Pollan’s latest book ‘How to Change Your Mind’ explores the history, usage, and potentialities of psychedelics as treatments for mental health. Pollan’s own enthusiasm for the topic is contagious and has inspired me to re-analyze my own experiences with psychedelics as well excite me for the legalization of psychedelic psychotherapy. A few years ago, a friend clued me into the psychedelic ayahuasca. Ayahuasca is a brew made from the combination of two tropical plants, one containing the psychedelic compound Di-Methyl-Tryptamine (DMT) and the other containing an MAO Inhibitor which temporarily blocks the brain’s mechanism for metabolizing DMT. Like LSD or psilocybin, DMT typically causes powerful hallucinations for those who consume it. For centuries, this brew has been ceremonially used by indigenous cultures and shamans in the Amazon for spiritual and psychological well-being. Since a 2006 Supreme Court decision, ayahuasca consumption is legal in the US within the context of the South American traditions that utilize it. I was both terrified and captivated by my friend’s description of his ingestion of ayahuasca with a shamanic group. He hallucinated an enormous serpent entering the crowded and dark ceremony space. The constrictor curled itself around his torso and squeezed him until light erupted from the crown of his head. Being the product of hippie-parents – these visions attracted me. And more captivating than the visions, was the clear emotional change present in my friend. As we worked together on a creative project, his enthusiasm and humor flowed freely. He easily translated his visions into metaphors for the struggles of his daily life. Fear and pain transformed into acceptance and healing. At the time, I felt stuck in life. Some of my closest relationships were frozen in conflict. My job as an audio-engineer was at a dead-end. My sense of enthusiasm about anything diminished. I had yet to discover the power of traditional talk-psychotherapy, so the prospect of transforming my mind and life by simply ingesting a drug seemed worth the risk. After some thorough vetting by the organization, the ayahuasca facilitators offered me a spot in their next weekend of ceremonies with their shaman. Before flying to Northern California for the ceremony, I read others’ online accounts of drinking ayahuasca. Most talked of the positive personal transformation following nightmarish battles with their own demons. Like my friend’s visions, much of the symbolism and imagery centered around the flora and fauna of the rainforest. Nets of vines, rainbow jaguars, and mischievous elven-humanoids. Almost everyone spoke of the nausea they experienced after ingestion. Many vomited during the course of a ceremony, though this purging was generally cathartic and meaningful. Symbolic of negative energy leaving the body. My internal cynic, normally quick to hack down anything resembling New Age Spiritualism, was tempered by my internalized protestant. It seemed appropriate that I needed to suffer to be happy. After driving deep into bucolic countryside, we arrived at the large converted ranch-home that was the ceremony space. Nestled within a grove of redwoods, I nervously chatted with the ~40 other participants before the ceremony commenced at about 9 PM. The dark room was smoky with incense and totally quiet as I drank 2 or 3 ounces of the disgustingly bitter ayahuasca. As the shaman began to sing and play a jaw harp, I felt no difference for an hour or so. So when a second round of the brew was offered, I drank even more. Gradually, I noticed a subtle sense of pleasure pervading my body and perception. Even as the climate in the room grew restless, I noticed feeling giggly and playful. Someone suddenly stood up, hurriedly ran to the door while vomiting into a plastic bucket. “Unlike that guy, maybe my night with ayahuasca will just be fun?!,” I naively hoped to myself. Wanting to hold onto my good vibes, I stepped outside to the cool and quiet yard abutting the redwoods. As I stood looking up at the stars and yawned, I noticed a disturbing distortion in the sound of my own breath. As if my bodily process had been poorly burned to a CD and was being played back to me. Then my jaw began to feel unhinged – like an egg-eating snake’s mouth. The stars above me trembled. Standing next to a rosemary bush, I was bewildered at these sudden changes. I had just a moment of confusion until ayahuasca hit me with the force of a punch to the gut. My legs gave out and I dropped to the soft grass, mere steps from the front door of the ceremony space. I laid in that spot for the next 3 or 4 hours. Because of LSD’s association with the counter culture movement of the 60’s, the FDA banned research for 30 years into the therapeutic use of psychedelics. After promising gains made in the 40’s, 50’s and, early 60’s, the field went dark. Some very dedicated and impassioned scientists kept the flame alive and have finally managed, in the past 20 years, to again research the mental health potentialities of psychedelics. Scientists now generally agree that the active compounds in psychedelics are acting upon the brain’s neurotransmitter serotonin. Serotonin became a household word in the late 80’s when a new class of anti-depressants Selective-Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors (SSRI’s) hit the market with the promise of alleviating human misery. 30 years of mixed results with SSRI’s has shown that we don’t understand the complexity of the serotonin system, including how exactly psychedelics or SSRI’s are inducing their effects. Thankfully, recent developments in the technology of Functional Magnetic Resonance Images (FMRI’s) have allowed scientists a real-time glimpse into the tripping-brain. Scientists were surprised that many parts of the tripping brain were less active than in daily-life. Specifically, there was diminished activity in a set of linked brain structures known as the Default Mode Network (DMN), a hub connecting an executive center of the brain (pre-frontal cortex) to the less-evolved brain parts involving emotion and memory. The DMN is most active when we are in self-reflection or meta-cognition – thinking about how we are thinking or feeling. In plain speak, the DMN is active when we are thinking about ourself. A sense of self or ego may be emergent from the DMN’s processing. This network takes the conflicting inputs from our visual, spatial, and other brain regions and determines what warrants attention by the ‘self’. The DMN’s primary task is to down regulate – to cull irrelevant bits of data from our awareness. Without the DMN and its ability to prioritize, our brain would be a discordant symphony without any self conducting. We are able to coherently move through the world because of the Default Mode Network. However, an over-active DMN may also be the source of depression, anxiety, and other mental illnesses associated with a distorted sense of self. As Pollan illuminates “The achievement of an individual self, a being with a unique past and a trajectory into the future, is one of the glories of human evolution, but it is not without its drawbacks and potential disorders. The price of the sense of individual identity is a sense of separation from others and nature. Self-reflection can lead to great intellectual and artistic achievement but also to destructive forms of self-regard and many types of unhappiness (pg. 304).” When researchers looked at the brains of participants who had ingested psychedelics they found a clear relationship between reported ‘ego-dissolution’ and diminished Default Mode Network activity. A reduction in depressive symptoms also followed. “‘I existed only as an idea or concept’ one volunteer reported. Recalled another, ‘I didn’t know where I ended and my surroundings began (p. 304).’” Research into the DMN and psychedelics attracted the attention of researchers analyzing the brain states of long-term meditators- those with thousands of hours of practice. These meditators also had abnormally diminished activity in the DMN, especially when in deep meditation where they reported transcendence of self – a dissolution of duality or no separation from subject and object. The brain states of experienced meditators looked remarkably similar to tripping brains. After dropping to the yard mere feet from the ceremony space, my mind lost control of the reality it had, up to that point, known. Seconds, minutes, or hours later a new awareness emerged with dramatically different perceptions than my waking-self. I was unable to move my body or focus my eyes, but my hearing was unnaturally acute. I could make out the whispers of other participants in distant parts of the large yard and became aware of the orchestra of the Redwood forest near my prostrate body. My ears were a gateway into another world and there was no separation between hearing and feeling. The wind bending the tops of the sentinel Redwoods and the cool, damp coastal air soaking into the forest floor. The tiny frogs in a nearby, unseen pond answering the elemental forces with a celebratory chorus. It was all inextricably linked. A feeling of reverence washed through me with each new gust of wind and chirp of frog. Yet another part of me was profoundly disturbed by my new state of awareness. It needed to control something – anything. It wouldn’t allow me to sink into the forest-web for too long before it demanded attention. When it successfully wrested control it demanded action. “Sit-up and do something,” it mandated without a clear vision. As I fought to assume a seated position, I became aware of how utterly terrible and insane I felt. Nausea and vertigo rolled through me as panic and despair filled my thoughts. I was convinced that I had done something wrong and needed to contact the authorities. They needed to imprison me for the crime of losing my mind. And my family needed to know how lost I had become. So far from home – so alone. [goya] My mind unearthed a relic from my subconscious: my distant, long-dead grandmother on her death bed. Demonic and alive imagery electrified her memory. Isolated, terrified, skeletal. There was no separation between her state and mine. Our collective existence was horror. It all reached a sickening crescendo and I vomited into the grass next to me, falling back to the earth in catharsis and sinking back into the grove of life. This cycle repeated several times over the course of the evening, though my sense of time was dramatically altered as I toggled between realities. The here-and-now was both a concrete reality and part of a terrifying, stretching-to-infinity continuum. In early 2017, researchers in both the US and UK were given permission by their governing bodies to study the effect of psychedelics on treatment-resistant depression – depression non-respondent to several different kinds of interventions (medication, talk-therapy, etc.). Globally, incidences of depression have been rising, so the remarkable results of the study were a pleasing surprise. A week after the study, every single volunteer experienced a reduction in their symptoms and 66% of volunteers were completely depression-free. 33% of volunteers remained in remission for 6 months. These results may sound modest, but compared to other forms of treatment they are stellar. They hint that unlike daily medication, psychedelics may only need administering once every few weeks and have none of the unpleasant side-effects of anti-depressants like weight gain or diminished sexual interest. None of the respondents reported an adverse psychedelic experience, like suicidal ideation or increased agitation as can happen with medication. And unlike the weeks or months sometimes necessary for talk-therapy and medication to show improvement, clients showed nearly instantaneous improvement after their trip (p. 376-377). While the quantitative data of the study showed statistical promise, the qualitative information proved to be just as rich. Through interviews with patients, researchers found that psychedelics broke the cycle of negative thinking and rumination characteristic of depression. Patients felt they had been freed from their mental prisons and had re-discovered connection with people, nature, and the world-at-large. Patients also discovered a broader spectrum of emotion – both good and bad – which gave them greater contentment and vitality. In the pre-screening process, patients were encouraged to face whatever difficult emotions or thoughts came up during their trips. Instead of trying to make bad feelings or thoughts go away, to face them and understand where they come from and what they’re about. The results of such coaching were dramatic. One patient who suffered from years of depression reported ‘You don’t cherry-pick happiness and enjoyment, the so-called good emotions; it was okay to have negative thoughts. That’s life. For me, trying to resist emotions just amplified them (p. 380).’ Clients re-experienced traumatic memories yet were newly able tolerate the emotions associated with them. Their trips seemed to help integrate disparate parts of themselves and encourage a brave and compassionate view of the self and others. Though the treatment shows much promise, it is not perfect. Most patients saw their depression return after 6 months, so psychedelics may represent an ongoing treatment rather than a one-time intervention. Though every form of mental health treatment (talk therapy, meditation, or electro-shock therapy) requires some amount of ongoing regimen. The brain is perpetually changing and growing, so like a garden it is reasonable to expect some ongoing maintenance and care of it. Pollan also notes that new treatments, including SSRI’s, usually show greater promise at the beginning of their introduction than once established. The power of placebo is real and psychedelics may be no different – only time will tell. However, if psychedelics continue to show promise in depression, addiction, anxiety, and PTSD, they may show that the myriad diagnoses actually share an underlying faulty mechanism in the mind. Different variations of the same illness. Pollan exposits the work of former FDA head David Kessler and his term ‘capture’ to describe the unifying component of the mind involved mental illnesses “...All these disorders involve learned habits of negative thinking and behavior that hijack our attention and trap us in loops of self-reflection (p. 383-384).” By decreasing activity in certain brain structures and connecting previously disparate parts, psychedelics may offer the brain a chance to forge new pathways – even after years of negative habits. This premise dovetails nicely with new wave theories of mind correlating mental flexibility with happiness. Psychedelics distortion of time, place, and self may be viewed as a key to unlocking the prisons-of-self characteristic of mental suffering. Pollan eloquently states, “When the ego dissolves, so does a bounded conception not only of our self but of our self-interest. What emerges in its place is invariably a broader; more open hearted and altruistic that is, more spiritual idea of what matters in life. One in which a new sense of connection, or love, however defined, seems to figure prominently (390).” After 3 or 4 hours caught between my ego and the web of life around me, ayahuasca’s effects diminished enough for me to stand up and walk back into the ceremony space. As heavy rain began to fall outside, I tumbled to my sleeping mat between my friends. As the shaman continued to sing and dance, my body began to shake – discharging the energy from my struggle. My friend wordlessly covered me with a blanket and I slept. Chuckling now as I remember my ayahuasca night -my view informed by years of psychological education and training - my egoic struggle seems like the wet-dream of a psychoanalyst. It is also so commonplace as to be cliché, but that does not diminish its importance. Immediately after the ceremony, I needed no intellectual or scientific understanding of my trip to feel the benefits. For a few months, life felt shiny and bright. I explored parts of my city and interests of mine that had been in plain sight, yet I had been too morose to explore. The challenges faced in daily life were now small in comparison to the challenge I faced during my night of ayahuasca. Life seemed effortless and my playful side returned with my friends and family. My new self-confidence also emboldened me to express to others what I had been containing for months or years. Fights happened, but they felt necessary and in the service of deepening the relationships rather than withdrawing from them. Over the course of a few months, my new perspective gradually diminished as the various difficulties of life swept me up and away. Though the insights I gathered have been reinvigorated by Pollan’s exploration in ‘How to Change Your Mind’ and given me two ways to perceive my trip. First, the scientific explanation that would see my trip as the product of DMT drastically altering my neural pathways. My Default Mode Network was temporarily disengaged by the DMT molecules binding to my serotonin receptors while the MAO-Inhibitor prevented the DMT from being metabolized by my body – thus prolonging my experience for a few hours. For seconds or minutes at a time, my DMN was disengaged so that new neural pathways were being stimulated by the cornucopia of sensory data present in the vibrant forest. Temporarily, I had the brain of a toddler that had never experienced the sights, sounds, and textures of a redwood forest. Yet, there was enormous internal resistance to pulling my DMN offline – a testament to the brain’s robust neural pathways that were bolstered by every single moment of my life I had identified with my ‘self’. The vomiting and other gastro-intestinal effects induced by ayahuasca might also be seen as a typical side effect of serotonin-based drugs. And now for the psychotherapeutic/spiritual/metaphoric interpretation. I was mildly depressed before this experience because I had over-identified with my ego or self. I was trapped in my mind’s projection of me in the future – one that had little hope or joy in my job or relationships. I saw little point in exploring the people or world around me because my self was convinced that they would offer no reward. Ayahuasca offered me a hyper-distilled version of my depression. A version that was not intellectual, but unavoidably felt. Like the ghost of Christmas Future for Ebenezer Scrooge (or Bill Murray), I was shown what life could be like if I continued down this path towards a lonely existence like my grandmother’s. I was also presented an alternative to this path –the natural world full of dazzling complexity and richness. The struggle between choosing either path, more than world’s themselves, was the most meaningful aspect of this experience. For it was symbolic of a choice I face in everyday life. How much to identify with the story of my self?

4 Comments

Sandra

12/27/2018 10:03:39 am

Thanks for sharing your ayahuasa experience! I didn't know that about Cary Grant--fascinating! Have you seen the documentary? I'd love to see more posts along this vein. :)

Reply

Joe M

12/27/2018 11:31:15 am

Wow! What a great and fascinating read. I love the way you bounce back and forth between your experience, and the research/theories of psychologists and practitioners. Keep up the great work!

Reply

Rebecca

1/2/2019 04:56:51 pm

Thanks for sharing your experience as well as for weaving in the science so deftly. I really enjoyed reading.

Reply

Paul

1/4/2019 10:41:29 am

I like all the threads you weave together in this. Enlightening, promising

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

David HixonMy ongoing exploration into therapy related topics. Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed